“Food is Not Just About Survival,” Says Kitchen Committee Organizer

“Food is nourishing and joyful,” says Sienna Ruiz.

Popular movement moments often generate iconic imagery. During moments of mass protest, photos of protesters squaring off with police, shutting down roadways, and chanting into bullhorns abound. For most of the public, movements can become synonymous with or even summarized by these images. However, those of us who have engaged with movements know that such moments are made possible by a web-work of unseen labor and solidarity. From art-making to transportation and care work, meaningful resistance has a plethora of moving parts that are rarely captured in viral photos. For example, if a group of people are going to share a particular task and space long enough, those people are going to need to eat.

The work of feeding organizers and protesters has a long history. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Georgia Gilmore opened a restaurant in her home that fed protesters and organizers, including Martin Luther King Jr., after being fired by the National Lunch Company for her activism. Since 1980, Food Not Bombs has offered free meals to community members and often provided food and drinks to protesters. More recently, the Kitchen Committee in Los Angeles was born out of worker solidarity and has grown into a thriving mutual aid project that serves community members in need while also supporting liberation struggles. I recently spoke with Kitchen Committee members Samyu Comandur (she/her), Amber Chong (they/them), and Sienna Ruiz (she/her) about the work of nourishing movements.

Kelly Hayes: Can you tell us a bit about the Kitchen Committee and the work that you all do?

Samyu Comandur: Kitchen Committee formed the night before the start of the Fall 2022 University of California academic workers’ strike, the largest strike in American higher education history. A group of us graduate students were excited to make the picket into a space for community care through all of our different experiences, skills, and interests in food. While serving the dozen Instant Pots worth of congee we had made for the first day, we realized how central food was to building meaningful relationships and bolstering picketers’ energy and morale. Cooking and sharing meals also created valuable moments of play and joy amid the precarious living and working conditions maintained by the university.

Early on in the strike, it became evident that despite setting a picketing requirement of 20 hours per week in order for union members to access strike pay, our union leadership had no plan for sustaining our health and wellbeing during a strike with no determined endpoint. We started to see Kitchen Committee–or Strike Kitchen, as we called it then–as a mutual aid project independent of our union and its resources, and keeping each other nourished during these unprecedented circumstances felt all the more critical. Every morning, we would fire up our collection of coffee makers and put out breakfast items for the morning picket shift. Then we’d serve Lunch at Bunche, where hundreds of people from the Bunche Hall picket line would gather for a community meal together. The artists in Kitchen Committee also used menu designs and punny recipe titles to share our commentary on contract negotiation updates and decisions made by union leadership during the strike–which was a rare opportunity for expression, given that leadership prohibited any posters that were not union-approved Unfair Labor Practice signage.

When our strike ended, we began transforming the infrastructure that we had developed during the strike into something more sustainable in the long-term. We loved working together and we wanted to extend this project, along with the relationship building it enables. But we also continued our work out of necessity— the contract that did get ratified failed to immediately meet people’s financial needs, due to delayed raises that hardly kept up with inflation, tiered pay structures that disadvantaged newly hired workers and workers at universities with less name recognition, and exorbitant fees for international students. We transitioned to stocking a community fridge on campus with free meals for anyone who requested them, as well as delivering meals to people in the West Los Angeles area.

As we have gotten accustomed to cooking in bulk, and often end up making more than enough food, we have also built partnerships with local mutual aid organizations, like Palms Unhoused Mutual Aid (another incredible West Los Angeles collective that Sienna and I volunteer with!) and Aetna Street Solidarity. We supplement their food reclamation efforts with any leftover meals of our own to be delivered at West Los Angeles encampments and temporary shelter programs at motels. I often think of us as caterers, offering multi-course meals in bulk to other mutual aid projects and movement work in Los Angeles.

Kelly: There has been a lot happening in your community in recent months, from the UCLA solidarity encampment to police raids, an academic worker strike, and a violent Zionist attack on Palestine solidarity protesters. What has your support work looked like during these events and how is your team holding up?

Amber Chong: A truly amazing team of undergraduate students organized the Food Tent when the UCLA encampment was first built back in April. With the bulk cooking experience and equipment that we gained from last year’s strike, and from the mutual aid work that we’ve done since, we were able to hit the ground running and cook together in our homes, or on-site with our portable stoves and grills. There were also so many delicious donations from community members and organizations all across LA. We’ve been continuing to provide meals since the police raided the first encampment, at teach-ins organized by the People’s University for the Liberation of Palestine, at other iterations of the encampment, and now, at the 2024 strike picket. Just like when we started Kitchen Committee, one of our hopes is that our food can make tangible the sort of collective caregiving that makes these efforts possible and that ultimately fuels this movement.

Kelly: I know that your group has been engaged in some fundraising work to help provide direct support to Palestinians who are currently in danger. Can you say a bit about those fundraising efforts and why this aspect of your solidarity work is so important?

Amber: Kitchen Committee puts food at the heart of our obligations to caring for the people around us. We want to keep pushing that sense of obligation beyond our immediate communities. We see our involvement in the UCLA encampment and recent strike as directly connected to our shared investment in the liberation of Palestine. While we know that this is a long-term, multi-generational struggle, we also know that there are ways that we can immediately and materially offer our solidarity. We are enormously inspired by Gazans who keep cooking and working to feed people despite the extreme duress and dangers posed by israel’s ongoing genocide. They remind us who we are fighting for and alongside, and also teach us about the power of food as a tactic for endurance and transformation. Supporting us as Kitchen Committee also means fighting for their wellbeing.

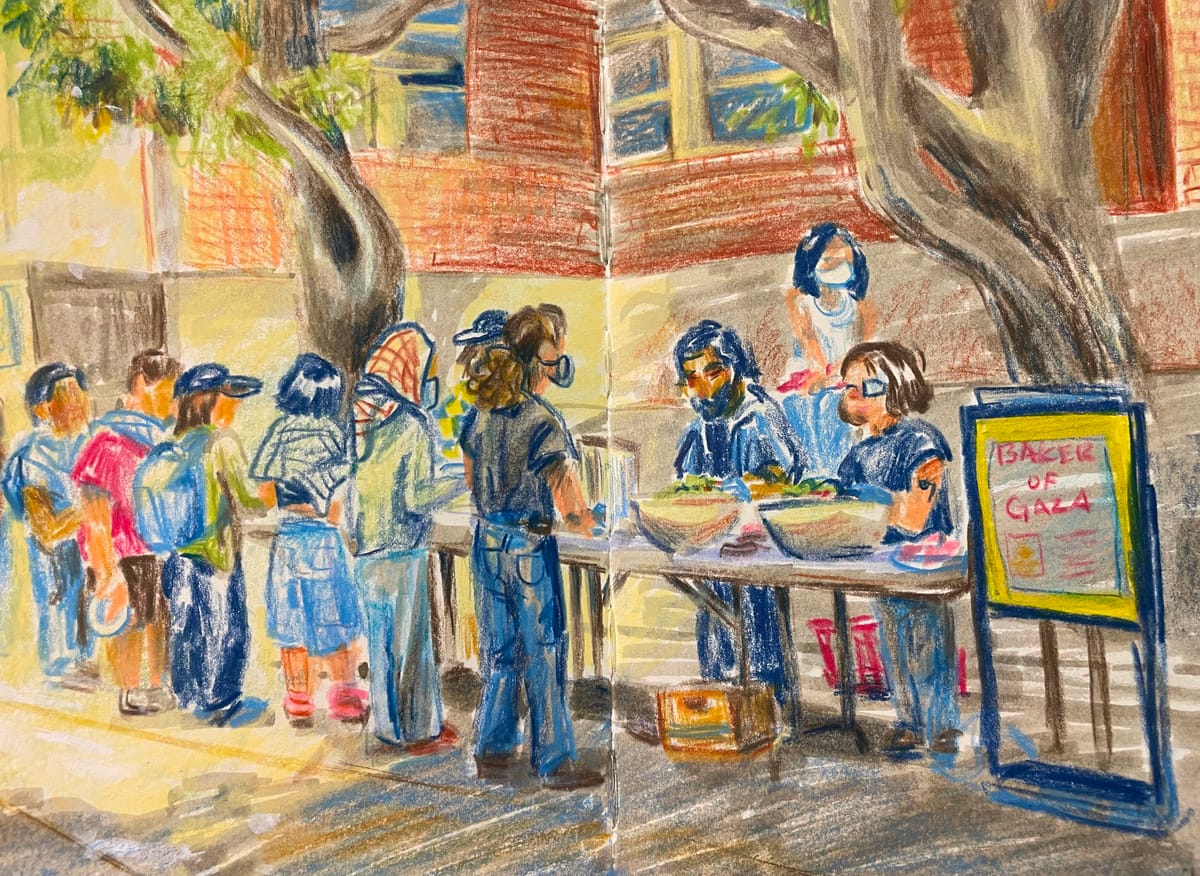

Currently, we are asking people to contribute to Ibrahim Abu Hani’s evacuation fund. Ibrahim Abu Hani is a baker and the owner of Batool Cake, which had three locations across Gaza. The main branch in Khan Younis was destroyed by an israeli ground invasion in March. He continued operating his bakery in Rafah to ensure that people would have cakes for their birthdays and weddings—even when living as refugees. Following israel’s targeting of Rafah, Ibrahim has fled further north with his family and baking equipment. He set up his bakery in a car mechanic shop, in order to bake free birthday cakes for children displaced by israel’s genocide against Palestinians. We encourage you all to donate to his GoFundMe and help temporarily evacuate the ten members of his family from Gaza, which will allow them to rebuild their lives somewhere safer and, hopefully, return to Gaza to re-open their bakery someday.

Kelly: I hear that you all have a new resource coming out soon. What can you tell us about the zine you've been working on?

Sienna Ruiz: We’re working on a zine to spread the word about Ibrahim’s fundraiser, share good bulk recipes for protests, and ultimately create a counter-archive of community care. We want the zine to challenge institutional memory that erases student movements by documenting how the Kitchen Committee has grown and transformed since it began. Starting from the 2022 academic workers’ strike, to continuing to make food for students and local mutual aid groups, to this year’s encampment and strike for Palestine, we’ve grown our pool of chefs and learned how to improvise and feed each other in the middle of extremely variable and stressful protest situations. We want to use the zine as a way to share what we have learned. We also want to push back against media narratives about the strikes that have focused largely on the union leadership over the demands of the rank and file workers, and those that have spread lies about the supposed danger of the encampments. We instead want to highlight all of the on-the-ground efforts students and community members that demand a more just world and enact it in the very protests themselves. Through the zine, we aim to think about how food, and the process of making it, is not just about bodily survival—like Ibrahim and the cakes that he creates for the children of Gaza, food is nourishing and joyful, a form of meeting community needs outside of the terms of the state or institution and turning towards one another instead.

Kelly: Is there anything else on your hearts or minds that you would like to share today?

Samyu: I see Kitchen Committee as such an exciting venue for exploration because of our constant fluidity. We have been quick to adapt to the many physical spaces we inhabit, as we respond to the rapid militarization of our campus. Through our solidarity encampment cooking, we have managed to send meals into spaces that are undergoing active police raids, showing up to these spaces without knowing how we will transport our cooking to them. This is new territory for us, and it’s been simultaneously nerve wracking and inspiring to see how we have adapted. Our active membership also ebbs and flows, as people’s capacity changes and as we build new relationships with other collectives. As three individuals, we cannot speak to the totality of what Kitchen is or could become. There are so many people that have gotten involved since the encampment and the subsequent strike who have transformed Kitchen into something completely different from where we began. We are incredibly thankful for everyone who has been involved with Kitchen, past and present.

Finally, I want to thank Kelly for giving us opportunities to reflect on our experiences in this newsletter. I first connected with Kelly and their co-author, Mariame Kaba, through an essay I wrote about Kitchen Committee, which they kindly published in their Let This Radicalize You companion zine. Let This Radicalize You has since been a crucial resource in shaping my approach to this work— Kitchen Committee in its current form would not exist without its influence. We are indebted to the perspectives they provide us from other campaigns, movements, and organizers, but most importantly, we are lucky to have the tools that LTRY gives us to ground us in how we cultivate a sense of interdependence in our community.