Lessons From Political Prisoners

"Lesson one is just shut up, learn, and listen," says former political prisoner Ann Hansen.

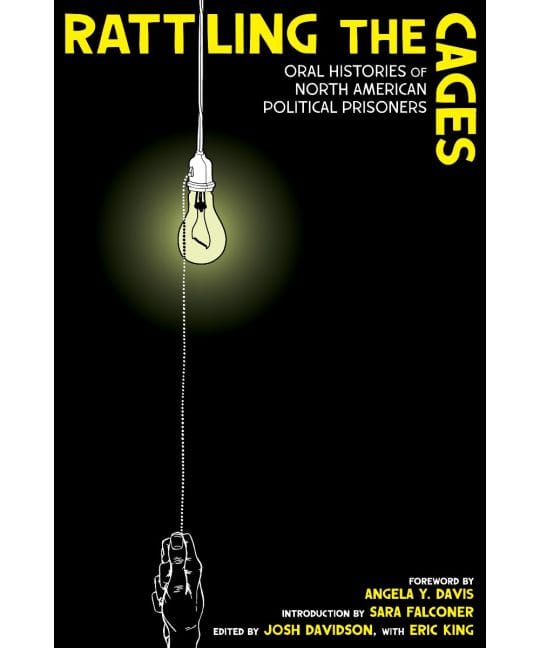

The following is an excerpt from Rattling the Cages: Oral Histories of North American Political Prisoners, edited by Josh Davidson and Eric King. A collection of oral histories, the book highlights the experience and wisdom of over thirty current and former North American political prisoners. This combined extract includes excerpts from multiple participants.

Marius Mason: It has been an interesting bid, and I have learned a lot about other people and about myself. There has been pain, and I have witnessed some terrible things that people do to each other when they are in pain. I have met some fascinating and worthy people and also a few jerks. It is all too easy to get lost in here, to drift in the waves of how things run in prison and to lose track of the world outside. But it has helped a lot to feel connected and a part of the community of resistance that links so many of us together through the outreach of some powerful individuals who make such a difference. Please know that your words matter when you write a letter to a prisoner—you send a literal lifeline to someone who might drown otherwise. Thank you for sending that hope and strength through these steel bars.

Linda Evans: In women’s prisons and jails, community is generally very vibrant and strong. The resilience and real community that women create collectively was remarkable. People are usually greeted with offers of shared commissary and hygiene items until your commissary account opens, shared food, cautious questions, and lots of shared opinions and advice. Because medical care is so abysmal in prisons and jails, women take care of each other when we’re sick. A friend of mine was diagnosed and was receiving chemotherapy in an outside hospital. Between her treatments, she was extremely sick, vomiting and unable to hold down food. Helping her survive the chemotherapy required a lot of care—shifts of friends checking on her, getting ice, or cleaning her cell.Another way we built community was through our HIV/AIDS awareness organizing and other educational efforts that also build leadership skills and friendships. Some of these efforts actually benefit the institution, so wardens may be inclined to allow them as a way to keep people occupied and positive. At FCI Dublin, prisoners formed a Council Against Racism to combat white-preferential hiring at UNICOR (prison industries) and to request translation of important prison documents into Spanish. We also organized an international festival with performances of music and poetry from every country with someone on the compound. But we lost our staff sponsor, and the club was disbanded by prison administration. Eventually, all the “inmate clubs” in the federal system were disbanded and are no longer allowed.

The AIDS work was crucial at that time to break through the stigma attached to being HIV+ and to educate people who were in such close contact with each other that they weren’t in danger. It was empowering, gave people something important to do to help others, and connected us with the outside world in a significant way—showing that women in prison could share their time, energy, and resources to fight AIDS and support people living with AIDS.

Ann Hansen: I think it’s very important for people going to prison—and I’ve said this so many times before—to just shut up, listen, and just observe at first. Because if you go in there and right away start talking—and I’ve done this before, because I tend to talk—people don’t like that. They see that as arrogant—you obviously think you know everything, and who are you to be sitting there blabbing away while other people are quiet? It is a good idea when you first arrive in prison or are transferred to another prison or part of one, to just shut up, learn and listen, because the people who are in prison are the PhDs of that world and you’d be surprised how much they know. Of course, there’s complete assholes in there too. It’s just like the outside. But still, it’s a totally different world, and you can’t just go in there and think you know it. I did think I knew a lot from having visited people and having read so much, but I really didn’t know anything.

Sometimes the people who are the least educated are the people who know the most about prison. People can be very compassionate who may not look like they are. You’ve got to learn a lot before you can go out in a prison environment and try to organize things. You’d be amazed at how many people think they can do that. And you’d be surprised at the shit that they get thrown at them from people. Within hours the people can smell it; they can just smell somebody who thinks they’re smarter than them. And there’s nobody to hate more than people who think they’re better than them because that’s who they’ve dealt with their whole life. Social workers and cops, and that’s the category they put you in if you act like that when you come in. So, lesson one is just shut up, learn, and listen.

Eric King: We wanted to honor the fact that life doesn’t stop when you’re inside; there are still joys and disappointments, heartbreaks and victories. We also wanted to give those political prisoners a chance to tell it in their words, to represent their lives however it felt best. Prison is a really shitty place, and it felt really important to document how ethical people navigated such an unethical environment.

I’m inspired by the people inside these pages, and I am extremely grateful that they’ve shared their time and experiences with us. There will be future political prisoners and abolitionists who will benefit greatly from the stories inside.