Sarah Kendzior: "Don't Give Up On Other People"

"If you still care, then I think there's still potential for this situation to be turned around," says Sarah Kendzior.

Television personality Mehmet Oz was sworn in Friday as the new administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In his remarks, Oz stressed the need to reduce chronic illness, declaring, “It is the patriotic duty of all Americans to take care of themselves. It’s important for serving in the military, but it’s also important because healthy people don’t consume healthcare resources.”

This dehumanizing, ableist framing—which blames individuals for the conditions that make them dependent on medical care—is in keeping with the broader eugenic overtones of this administration. We’ve heard similar rhetoric before, including Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s false claim that “If you are healthy, it's almost impossible for you to be killed by an infectious disease in modern times.” These narratives are designed to justify the abandonment of anyone deemed at fault for their health challenges or too “flawed” to deserve care.

This administration's politics of disposability often bring to mind the words of my friend Sarah Kendzior, who wrote: “When wealth is passed off as merit, bad luck is seen as bad character. This is how ideologues justify punishing the sick and the poor. But poverty is neither a crime nor a character flaw. Stigmatize those who let people die, not those who struggle to live.”

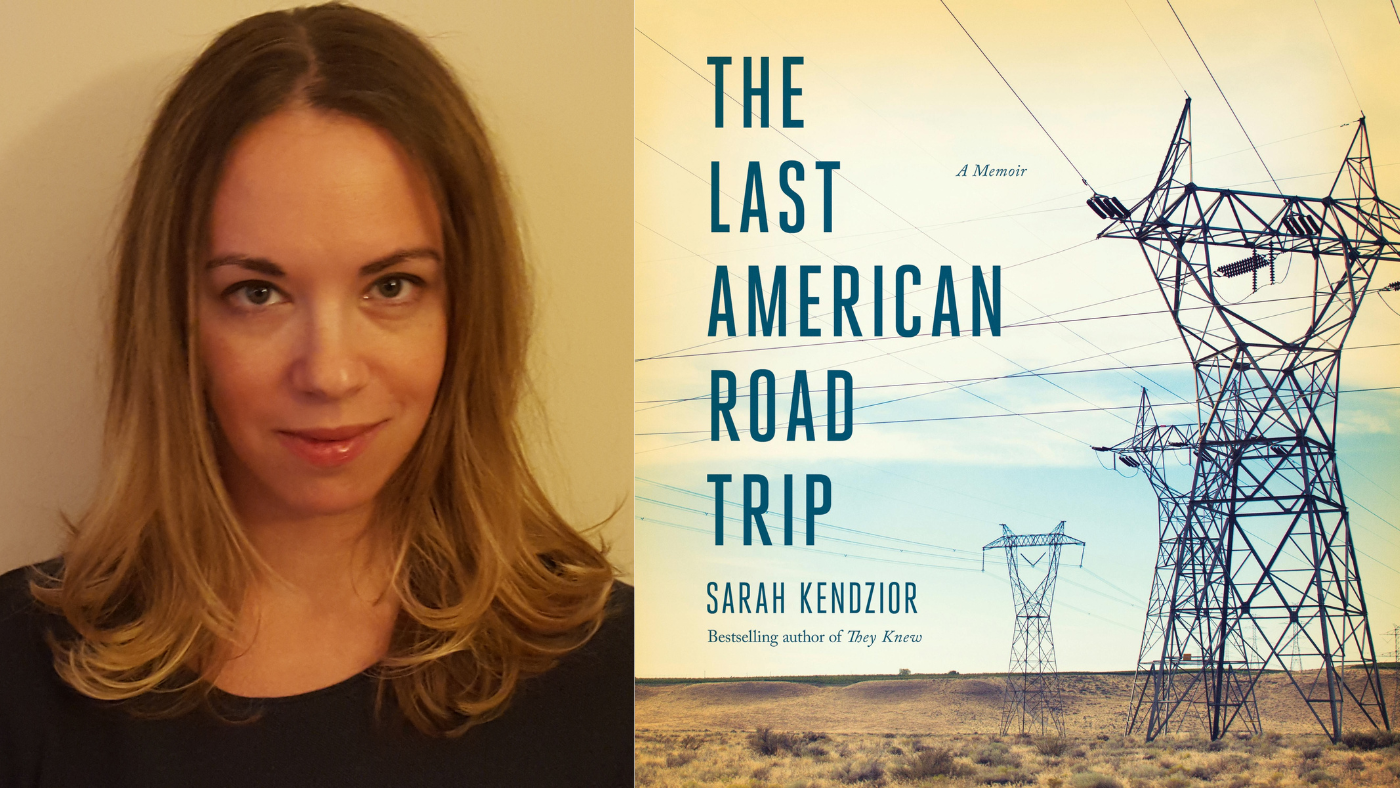

Sarah is the author of the bestselling books The View From Flyover Country, Hiding in Plain Sight, and They Knew. I am currently reading Sarah’s latest book, The Last American Road Trip, which feels like a long and thoughtful conversation with an old friend. I recently caught up with Sarah to talk about her new book, the mess we’re in, and how we can hold onto our humanity in these times.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Kelly Hayes: This is a pretty bleak moment in US politics. As someone who has studied authoritarian governments around the world and chronicled the progression of the mafia state here in the United States, how would you describe our present situation?

Sarah Kendzior: This is as bleak as I have seen it, and I realize that every time you ask me this question, that is my response. That's because we've been headed for this culmination for a very long time. I've been warning about Trump specifically for a decade, and before that I was warning about the conditions that allowed him to even be a "legitimate" candidate for office in the first place, despite his history. This institutional rot, deep-seated corruption, the flow of dark money through everything—and now we've reached a point where there's no pretense of attempting to make this a democracy. There's no pretense of officials being responsive to the people that they serve. Institutions are folding very quickly, obeying authoritarian whims and all of that. It's very hard to see because the end result is mass suffering and it's the suffering of people who are already vulnerable. Those are the targets.

Within that, though, I am glad to see there are people fighting back. I think often the people who are fighting the most, we hear from the least, because they're fighting a strategic battle. There are a lot of places, especially where I live in Missouri, where we've been accustomed to these kind of laws and this kind of harassment and oppression from the government for a very long time, and people have learned how to operate in a stealthy way, and I don't even mean things like protests or things like that, but mutual aid and communities reaching out to each other, providing information to each other, stuff like that. So it's still there, but I think the fact that it has to remain somewhat hidden gives people the impression that there's less of a resistance than there is. And I think in general, people, while feeling beaten down, still are willing to fight for what we have left, because it does mean so much to them, and they now see the magnitude of this potential loss.

KH: What are you most worried about right now?

SK: Oh my god, such a long list. I have a lot of nightmare situations in my head about the long-term direction where they're going. One of them is the surveillance state and the role of technology. Within that state, the ability of the government and corporations and tech companies to merge in a such a way that you are being spied upon, and if you express certain beliefs or sentiments, your ability to travel, get a job, get a loan or use basic facilities could be compromised—something akin to China's social credit system. That's one thing I'm worried about, because they are headed in that direction.

The open insertion of people like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, et cetera, is I think a dire attribute of this administration that wasn't quite as explicit in the previous one.

I'm very worried about pushes for partition. I've been talking about that for a long time. The model that this administration has always embraced has been the collapse of the Soviet Union and the aftermath of that collapse in the 1990s, where a lot of oligarchs basically saw what was left of the Soviet Union, particularly the authoritarian states that were once republics and became independent states, as just land masses to strip down and sell off for parts. You see this obviously in Russia, but it happened in Azerbaijan and elsewhere. It's a lot easier for somebody to carry out a plan like that if a country is divided into pieces, which is why we've heard a lot of like, oh, “the South should just secede,” that kind of rhetoric.

If the United States falls apart, if it falls into separate regions, or Texas or California or another large state leaves, that will make this enormously easier for the oligarchs’ agenda and goals. And I hope that folks see through that.

KH: What you’re saying about surveillance makes me think about the push to end so-called “information silos” within the federal government, like the push to merge IRS data with DHS data, for the purpose of hunting down immigrants. Under the banner of reducing supposed fraud and waste, and increasing efficiency, DOGE is trying to centralize information in ways that will create a kind of digital panopticon. And there are just so many things happening, and so many immediate concerns, like the way this decentralization will harm undocumented people, that I think a lot of people are missing the long game. As you’ve said, this information being centralized within the government, as the government partners up with tech oligarchs, is setting up a system where we are all under a microscope, and can be targeted in any number of ways, at any given time.

If you think about the way Elon Musk talks about people who aren’t part of his chosen elite, calling people “NPC”—it’s a kind of dehumanization. Every fascism has its subhumans, and for Elon Musk, generally speaking, humans are subhumans, because life is a video game, and if you’re not one of the people driving the game forward, you are a nothing and a nobody, and the game should be hacked in ways that make you easier to control.

And as far as partition goes, I think what they’re really setting the stage for, with this agenda of withholding funds for things like disaster relief, is to create zones of vulnerability and desperation where corporate forces can come in and billionaires can “rescue” a place in particular ways, in exchange for really taking over the area. That’s something I have been expecting for a long time. I think that’s how Curtis Yarvin’s “patchwork” of corporate fiefdoms managed by monarch-CEOs happens, if it does happen. It happens through organized abandonment and privatization at the scale of a kind of mini nation-building.

And to me, that kind of corporate usurpation feels really plausible under this administration, if it accomplishes as much of its agenda as it would like to.

SK: Absolutely. And this is a very long-term goal. A long-term plan influenced, I think, by what happened in the aftermath of the Soviet Union. But we’ve been on this road since Reagan and even before. And one of the biggest warning signs for me when Biden took office was the Postal Service—the fact that Biden did not fire DeJoy. There seemed to be this ongoing move to privatize or destroy the US Postal Service. And so I watched, during the last four years, this abandonment of key US institutions that do things for the public good.

I don't think Trump's second term would've kicked off the way it did if so many hadn't been placated during the four-year interval, where they accepted a lot of things during that four-year time that they never would've accepted under Trump. I mean, we just explicitly saw that. There were mass protests during Trump's term. Under Biden, a lot of these same actions, abuse of immigrants and migrants, for example, were taking place. The facilitation of genocide was taking place. And if you criticized it, people who would applaud you for criticizing it under Trump would get very angry at you, like, "How dare you? It's the Democrats that will save us."

I wish that there was a more thorough examination of what has happened in the last four years, both within the Biden administration, but also among the right wing behind the scenes, because often they were just openly planning this. You had people like Christopher Rufo confessing plans. You don't get a gulag for Americans in El Salvador out of the blue. People worked behind the scenes to make that happen. We had Trump's first term as a template, and we knew their ambitions and they wrote them down. Why was there no effort made to plan against it?

What will we do if Trump is reinstalled and they take power to ward all this off? And the thing that frightens me is that I think a lot of Democratic officials or others in our institutions just are fine with it or had no inclination to try to ward it off. That, or the denial was so deep that people thought, Oh, it'll come for others, but it won't come for me. I'm at Harvard, or one of those other elite spaces. And I'm not trying to rag on people who might have just gotten fired or lost their grants. We're seeing a lot of really horrific things happen to innocent people within these institutions. And of course among them are the international students, who are being unlawfully detained, deported, having their civil rights violated. But I think that a lot of these big power brokers, they thought they were somehow above all of this, but no one really is.

It is a tiny little group of people, just the ones you've said that want to invent these city states, where everything is technologically connected and monitored and everyone is surveilled and made into some kind of ideal subject. And I think this correlates with the rise of AI and its replacement of human creativity, which they're desperate to stamp out. They want to stamp out human creativity and they want to stamp out accurate history.

They want us to forget our own humanity, to surrender our humanity and to not know what it means to be a human being. Because if we feel less human, if we see ourselves that way, if we see other people that way, then we're more willing to accept the idea that certain people are disposable. And that's the main idea that they're trying to bring home now. But they've been, I mean, my god, they've been trying to normalize that since the dawn of this country. But there's been quite an uptick in this dehumanization, in recent history, including eugenicist rhetoric, since about 2022—the backlash to a lot of the big movements of 2020, and also a backlash to a lot of the COVID precautions. A lot of people are traumatized and misinformed. Some people see a powerful movement forming, and they feel like they would rather be on the side of power. They would rather feel like they are among the powerful than among the targeted. It's a classic trajectory towards authoritarianism, and unfortunately it's one that we've seen in our country in the past, collectively practiced. And now, the net has been widened and it includes almost everyone in terms of who they are seeking to capture.

KH: Every day I get messages from people who are frightened and strategizing around their safety or the safety of their community, or trying to figure out how their organization can survive what's coming. A lot of people are shaken and hurting. I told a friend yesterday that more and more often I feel sick after a long stretch of reading. And that feels significant to me, because I have been reading about a lot of disturbing stuff for a very long time. What advice do you have for people who are trying to hold themselves together emotionally right now?

SK: It's very hard. I've been studying these things my whole life. This is what I studied getting a PhD before I moved back into journalism—totalitarian and authoritarian states. And so I'm used to reading about these very dire things. Then I've read about them in a US context, and I've warned of their impending rise for the last decade. But that doesn't make any difference in terms of how it feels emotionally. It digs away at your soul. It digs away at your stamina, your ability to be resolute, because what you're watching is just mass human suffering. You're watching people suffering at scale, and you're watching people suffering individually, and then you yourself are also suffering as a target of it. If you have elderly parents, you're worried about Social Security. If you have kids in public school, you're worried that they're going to close. If you have a disability, you're terrified of what the government is going to do under RFK Jr. And the fact that we've had this attack on empathy over the last three to four years, where they've really tried to normalize a lot of cruel and dehumanizing behavior, I think it makes people feel abandoned and alone, I think to some extent, because people have been encouraged to abandon others.

So I guess, what I'd say here is: I think everyone is feeling this. There is a sense of separation and isolation. Even social media has splintered. But more than that, I think there's a level of self-censorship, of internal censorship, that wasn't there before. And particularly, people might not want to express the pain of the moment, because that pain is a vulnerability, and you don't want to give your opponent a sense of what your vulnerabilities are when you know you may be a target of political persecution. That, and you also just don't want to be subject to the cruelty of other people, who feel like they need to weigh in on what is a sincerely devastating emotional time.

And so I don't take breaks from the news per se, but I've always made a point of just getting offline for hours at a time each day. I do a lot of crafts. I do a lot of stuff outside. I've been making a lot of things. I do all sorts of textile work like embroidery and weaving and basket making and stuff. As this administration came in, I kept doing it more and more and wondering, why am I spending so much time making a basket out of pine needles? But then I keep thinking, I've made something. I've made something that's beautiful, it didn't exist before, and now I've made it and now it's there. And now I can give it to someone, and that person will be happy. They'll have a little surprise in their day. It's a small thing, but I've been sort of clinging to that. It's just a mode of behavior—just trying to bring things that are beautiful into the world, give them to others, check in on others, and just value the time we have with friends, family, and our community.

I've also been looking out for what is happening to my community in particular, because I am very worried about the defunding of public services and of schools, and what will happen to vulnerable people. I live in a state and a city that is already impoverished in a lot of ways, and that has long been a target of extreme right wing governance. In fact, Missouri is the state where they experimented and tested a lot of these policies. So we're experienced, but like I said, that doesn't take away the pain of it. So I guess, I don't know whether it's reassuring or not to know you're not alone in your pain, because obviously it's not reassuring to feel this level of pain. But I find it reassuring.

I'd rather we were all happy together, but I'm glad that a lot of people still feel compassion. When you see that people are upset because they feel compassion for those who are targeted and those who are detained or deported or whose rights are being stripped away, that shows a refusal to give up. It shows a refusal to give in. So even if it just feels like a scream of desperation, when you're still feeling that, you're expressing that it means you still care. And if you still care, then I think there's still potential for this situation to be turned around. If people refuse to surrender their humanity, I think that we are still able to fight back. We might not win, but we can continue to fight. And sometimes that's the more important thing.

KH: I really appreciate what you’re saying about compassion, and how the pain we feel when people are suffering is tied to our humanity, which is something we have to cling to and fight for in these times. I don’t think enough people recognize how the normalization of human suffering and disposability happen. When you stop caring about any group of people and their suffering, you lose part of your humanity, and you also become more vulnerable to the violence they’re experiencing. In this country, we’ve done that with imprisoned people for generations—and a willingness to ignore that system and those conditions has left people susceptible to violence they’ve learned to ignore. Now, Republicans and a lot of Democratic officials want us to stop caring what happens to immigrants, and to trans people, and to just throw more and more people under the bus, and eventually, the more you accept this, you’re just not a person who values or defends life anymore. Life is not precious to you. You have dehumanized others and yourself, and now everyone is disposable, and you are part of that culture. This is how that happens. And we have to rage against that. All of this talk about political expediency is just expediting the loss of our humanity.

The fascists want us to be consumed by self-preservation and self-concern alone, because that leaves us weak and isolated. That’s what empowers them. Our political potential is grounded in solidarity, now and always.

Now, let's talk about your new book, The Last American Road Trip: A Memoir. I have been reading this book and I absolutely love it. It's beautifully written, which is no surprise. When you talk about the Mississippi River and Mark Twain, weaving in so much history and political analysis, I really feel like I am on these road trips with you, having these conversations in a car or in a canoe. Can you talk about why you wanted to write this book and what you hope people get out of it?

SK: Well, what I hope people get out of it is a desire to protect the places and people of America during this terrible time. It's a book that I wrote about taking my children all around the US on the road to see national parks, historic sites, interesting places—starting at around 2016, going up to 2024—because I was very worried that these places were going to be destroyed, either through political force or by climate change. And I wanted my kids to experience this country through their own eyes, not through some sort of lecture by me or some sort of memory by association, but directly. And the beautiful thing about driving, especially when you live in Missouri, when you live in the center of it all, is that you see the landscape change, you interact with all sorts of different people. You see that this is a tremendously diverse country, and that's why it's, I think, the most interesting place to live in the world.

Really seeing a place has the power to destroy stereotypes and generalizations before they even begin. And it was important for me as a mom, for my kids to have that kind of experience, to stay curious, to stay open-minded, and they are. In that regard, my efforts succeeded. But of course, the book gets released now. I wrote it in 2023. It's getting released as there is an open attack on things like national parks. And so I think it reads differently now than it did six months ago. There were some advanced reviews where people thought I was being too pessimistic or maybe too hypervigilant, and I obviously was not. But that breaks my heart. I want very badly to be wrong. I've wanted to be wrong the whole time. My theory in taking these trips was like, well, if I'm wrong, we just get a lot of awesome vacations out of this, and that's a good thing.

But I am glad that I wrote it down because the other crazy thing with this book is that there are a lot of stories of American history in it that would undoubtedly be censored under this government's so-called anti-DEI strategy, where they basically try to erase anybody who's not white from American history. So if I'm writing something that should be a fairly factual and benign historical tale like about the man who first mapped a Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, who was an enslaved Black man, that individual is going to be erased from the websites and official narratives of American history. I mean, that doesn't mean it's going to get erased in general, but I'm glad I wrote this when I did.

I also really needed to get away from writing these very, very dark books about political corruption. I wanted to write about what I love and what I'm fighting for and what I value—a lot of which is my family and nature. It's a lot of simple things that are part of everyday life that are in danger of being taken away.

And for those wondering about this, yes, this is still my kind of book. I did take my kids to the airport where there was drug smuggling for Iran-Contra. So there are some things in there that are similar to my other books as well—lots of field trips for the kids. But I needed to write something more personal because I felt like we'd reached a point where I'd said everything I could kind of say about the broad scope of political corruption and impending doom.

I wanted to write about what mattered. And one thing that was subconscious, I guess, but it kind of chills me, is often in countries where authoritarianism has tightened its grip, you see journalists who had been covering things in a less personal way revert to the personal. Anna Politkovskaya in Russia began to do that. And she began to say that feelings are the most important thing, because her entire chronology of time in her head had become jumbled from living under the early years of Vladimir Putin. But she knew that what she felt, her love, her protectiveness of the victims of that government, those things were real and they couldn't be taken away. They could only be surrendered. You could only surrender your compassion or your imagination or your tenacity. They can't take those things from you. And so I think some of that seeps into the book. I wanted to find things that no one could take from me, whether they were personal attributes or just physical places that my children could see. Things like being able to see the Milky Way—these sorts of collective experiences that mankind had until very recently, when industrialization stole them. And I didn't intend for this to happen, but the last National Park we visited in the book was Death Valley. And we were out on the dunes looking up in the Milky Way, and then suddenly our vision of it was marred by Starlink, just slithering along. And so this shared moment of communing with nature was interrupted by the creations of Elon Musk. I didn't know when I experienced that, or wrote it down, how that moment would resonate now.

I hope that this book shows people things that are worth fighting for, and that we can find beauty in the wreckage, and should take nothing for granted.

KH: Is there anything else you would like to share with or ask of our readers today?

SK: Just know that it is normal to feel the pain and despair that you may be feeling now. Don't let people lecture you about it, but also don't give up on yourself, and don't give up on other people. Because I don't think that we are in a hopeless situation, I think it's just going to take an incredible reservoir of strength, and that locating that strength within yourself can be difficult. But I think that whatever way you find it, which I think is unique to every person, try to get there, because we need you. If anyone is making you feel like you're disposable or that your humanity can be debated, disregard that entirely. We need you here.

Organizing My Thoughts is a reader-supported newsletter. If you appreciate my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber today. There are no paywalls for the essays, reports, interviews, and excerpts published here. However, I could not do this work without the support of readers like you, so if you are able to contribute financially, I would greatly appreciate your help.